WELLNESS

SYSTEMS

CULTURE

Full steam ahead for global catastrophe?

Investors, shareholders and even customers aren’t what they were in the nineties.

nvestors, shareholders and even customers aren’t what they were in the nineties. The future of a business’ success is now tied to the authenticity of its brand's values. Although some key stakeholders may still rock huge shoulder pads and too much hairspray, their coffee cups are now made from vegetable derived materials, and they increasingly drive electric cars.

Flexi-Hex have transformed the idea of packaging.

And while they may still own some frankly unfashionable choices and opinions, we can be in no doubt that the consensus—and the majority of consumer choice—is pulling firmly towards more equitable and sustainable practices in all walks of life.

At the same time, the writing is on the wall for ‘business as usual’: even if we wanted to plough on, it is clear that we cannot continue to seek short term profit at the expense of the wealth of future generations. But an alternative model is still TBD, which creates no end of anxiety. What do we do before we realise utopia?

Whether COP26 was a success or failure will be determined by how we collectively deliver on a complex range of targets and goals.

After COP26, which seemingly failed to respond to the stark warnings outlined in the Sixth Assessment Report from the IPCC, many of us have been left wondering what’s next? How do we avert climate catastrophe and slow the staggering levels of habitat and biodiversity loss that threatens our world and way of life? Whatismore, these are seemingly insurmountable challenges for world leaders, so what can businesses do?

Luckily, there’s some good news: the solutions are out there and they are multiplying. So it’s an opportune time to remind you all that you’re not alone. Penny Black is here to help you answer such timeless questions as: how do we, as businesses and as people, effect real change? Where do we even start to contribute?

This blog looks at how a HUX materiality assessment is an ideal jumping off point for businesses looking to address the challenges of the day and create value for all. But before we look at what material issues and materiality assessments are, we start by considering the central role of brands in all of this.

Photo via Cosmos.so

Brands that generate more than profit

While a business’ first steps towards sustainability can be intuitive and easily implemented—think banning plastic straws and diversifying recycling bins—most leaders quickly realise that meaningful impact is not only difficult to achieve, but that the hard work starts when trying to select what exactly to work on.

We all intuitively know that changes must align with a business' strategic goals—including bottom line—but this is as far as gut feeling and most MBAs take us. So, where next? First there is an obvious and urgent need to prioritise what a business can do to help avoid the projected outcomes of the anthropocene.

The greatest questions, therefore, that HUX wants to help you answer are: where do we start? What does action on these topics really mean for our business and our stakeholders? And, when we do get started, how do we know our actions are actually of value to the planet, its people and, of course, the business too?

“Those topics that have a direct or indirect impact on an organisations ability to create preserve or erode economic, environmental and social value for itself, its stakeholders and society at large.”

— Global Reporting Initiative (GRI)

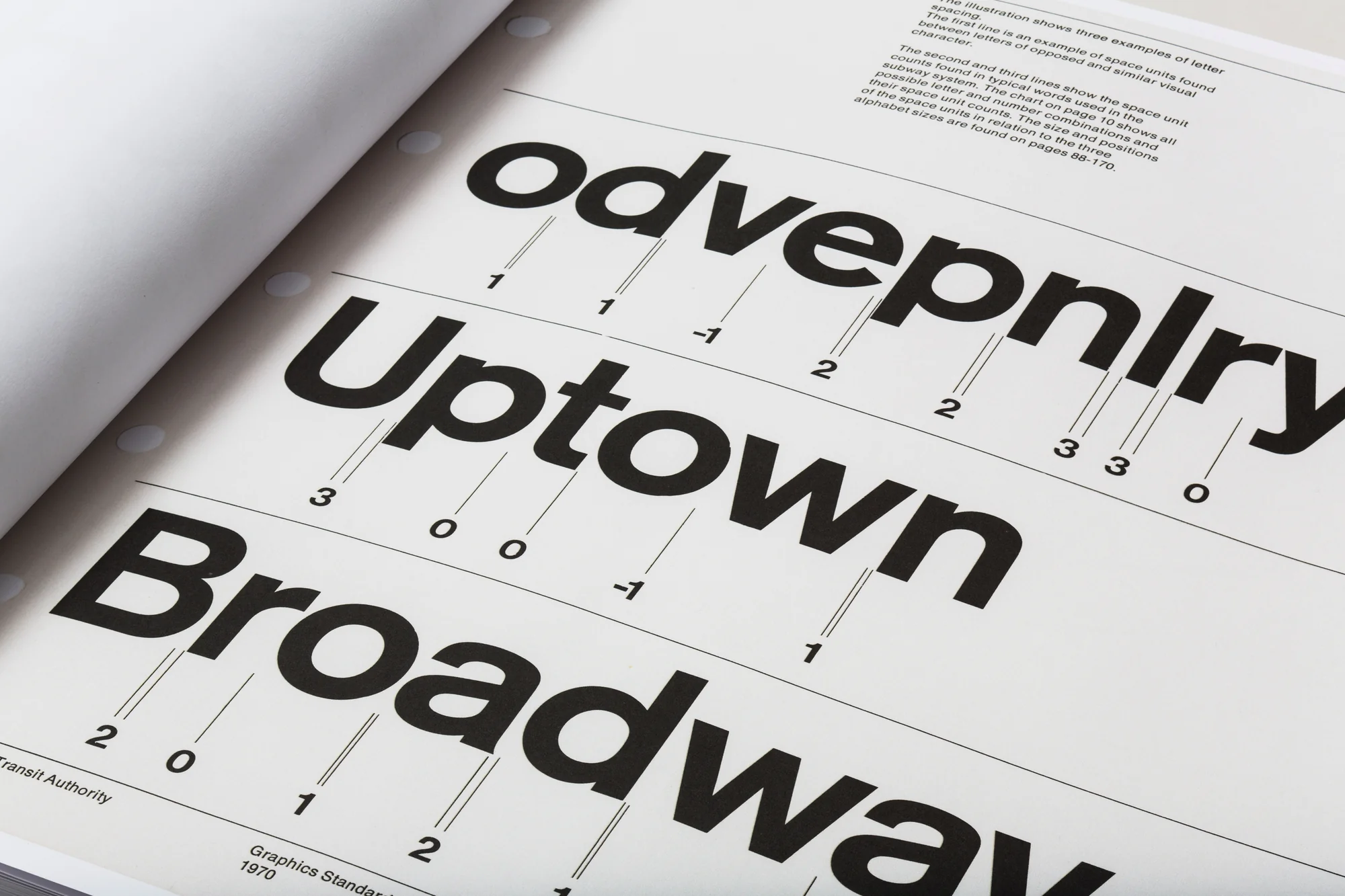

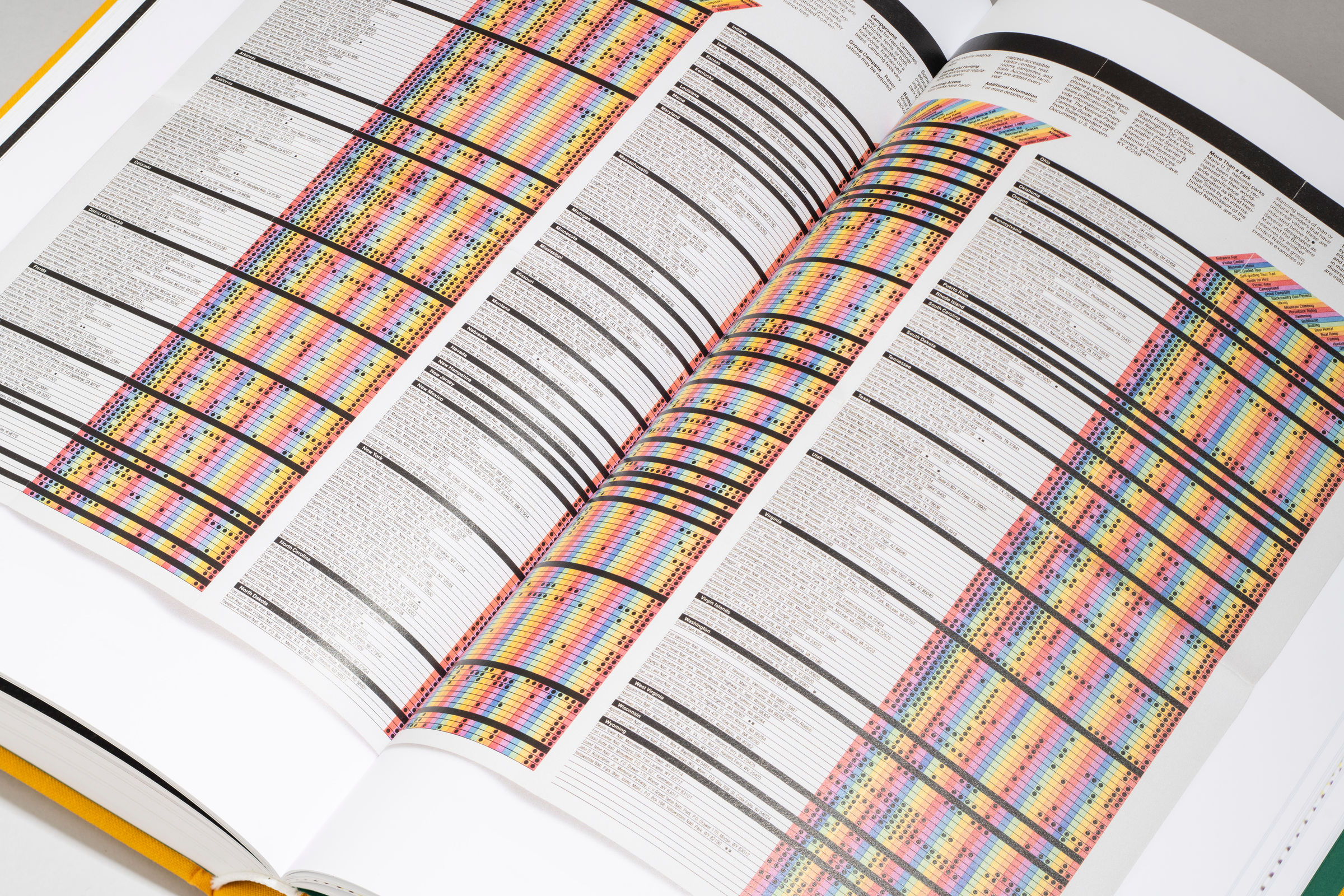

1970 New York City Transit Authority Graphics Standards Manual via https://standardsmanual.com/

What are material issues?

A business’ journey towards sustainability begins with identifying material issues associated with its business that impact people, planet, industry, and brand. Material issues include environmental, social and governance topics (hence ESG) that are likely to affect the financial condition or operating performance of businesses. These topics can be business specific or industry or sector wide and can be used as cornerstones of brand campaigns and reporting.

The issues that are most material to a business are deeply embedded within, or crucial to its operations. For good and for bad, the way a business deals with these issues are ultimately reflected in the way its brand—as an idea and the role it plays in people's lives—is truly perceived. Transparency is critical if transition to a sustainable future is to be credible.

Any distance between a business’ operational reality and the values projected by its brands appear as inauthentic and even deceptive to increasingly critical ‘activist’ consumers. If not managed appropriately, these material issues will diminish brand value, impact company performance and profitability, sometimes irreparably.

Parks Standards Manual via https://standardsmanual.com/

The Materiality Assessment

Using recognised international benchmarks and standards, a HUX materiality assessment is an external review that identifies and then prioritises issues that are most material (read most important) to a given business or organisation and its brands. The findings of a HUX materiality assessment are used to guide strategy and reporting, and make a case for where to strengthen a business's operations sustainably and transparently. A goal of every one of our assessments is to provide the basis of a credible plan on which a business can take concrete action.So, how do we know which issues are most material and need to be addressed? We ask the people that know the most about the issues that are impacting your business. Ultimately, this is an exercise in stakeholder engagement, designed to find what is crucial to your people and to the stakeholders that matter the most to your business and brands.Because transparency plays a large role, it’s an exercise that demands the input and guidance of senior management, staff and key stakeholders. Due to the delicate nature of issues included, a materiality assessment is ultimately an exercise that the organisation may find difficult to complete on its own. This is where Penny Black comes in.

The open-source CSS framework, Tailwind.

Type 3: Design Systems as Products

Material Design. Lightning Design System. Shopify Polaris. The system itself becomes the product—maintained, versioned, documented like software.This addresses scale. Multiple teams, multiple products, inconsistent experiences. You're big enough that informal coordination doesn't work anymore.What it looks like: dedicated system team, public documentation sites, versioned releases (v1, v2, v3), adoption metrics, support channels. These systems are products with users, roadmaps, and SLAs.The yoga parallel: established lineages—Ashtanga, Iyengar, Vinyasa. The sequence is set. Teachers worldwide practise the same structure. Transmission at scale requires clarity. The system holds so practitioners can go deep.Most small teams don't need this. If you're under 50 people, Type 2 is enough. Type 3 is for organisations where coordination across teams becomes the bottleneck.

Ecommerce at scale. Shopify Polaris.

Type 4: Design Systems as Process

Governance. Workflow. "This is how we work." The system isn't just components—it's the process that creates, maintains, and evolves them.This addresses chaos in decision-making. Nobody knows who decides what. Changes break things. No clear path from idea to implementation.What it looks like: contribution models (how to add components), review processes (who approves changes), communication channels, change logs, RFC processes. The Design Systems Handbook from DesignBetter.co (2017) covers this stage in detail.The yoga parallel: sangha (community) and teacher-student lineage. The practice transmits not just through poses, but through relationship, correction, evolution over time. The teacher removes guesswork. Students follow. Attention goes to execution, not choreography.You need this when the system exists but adoption is patchy. Teams work around it instead of with it. Process without bureaucracy—that's the balance.

Design Systems Handbook via DesignBetter.co

5: Design System as a Service Systems as Process

The design system team operates as its own entity. Internal agency model. Other teams are clients. The system is a service provided to the organisation.This addresses the system treated as an afterthought—documentation nobody maintains, components that drift, no clear ownership.What it looks like: dedicated team (designers, engineers, PMs), SLA commitments (response times, release cycles), support channels, office hours, internal training programmes. Thinking in Systems by Donella Meadows (2008) informs this stage—systems as living entities that require care.The yoga parallel: guru or teacher as a dedicated role. Teaching isn't a side practice—it's the practice. You can't scale transmission without dedicated practitioners who hold the lineage.Most organisations reach this stage around 100-500 people. Below that, it's overkill. Above that, it's essential.

Slack, Notion, Jira or Linear help with system team tasks.

Type 6: Design Systems as a Practice

Most mature stage. The system isn't a thing—it's how the organisation thinks. Repeatable, embedded, cultural. Design systems thinking permeates everything.This addresses fragmentation at scale. As organisations grow, coherence collapses unless systems thinking is woven into culture.What it looks like: systems thinking as default, cross-functional fluency (everyone speaks system), self-reinforcing culture where teams contribute naturally, practice over project (ongoing, not episodic). Tim Brown's Change by Design (2009) and Meadows' Thinking in Systems explore this level—where structure becomes second nature.The yoga parallel: lifelong practice. You don't "finish" yoga. The mat is where you return. Daily. The practice evolves as you evolve. Structure that breathes.This is where HUX operates. Systems at play—not rigid rules. We teach teams to build structure that holds without feeling rigid. Operator-led workshops. No-code tools. Shared language that removes repeat decisions.You reach this stage when the system is no longer a project. It's how you work. Version 87, not version 1.0. Airbnb sits here. Shopify sits here. Most teams don't need to aim for this immediately—but knowing it exists helps you understand the path.

Airbnb Design System evolution.

Universal Principles (Across All Types)

These apply regardless of which type you build.

Foundations before flow. Visual language before components. Tokens before UI. Radhika won't let me attempt advanced poses until my stance is solid. Same principle. Don't build what's impressive. Build what holds.

Repetition without rigidity. Reuse reveals what works. I practise Sun Salutation A daily—same twelve poses, never identical. The structure stays the same. What I notice within it changes. Good systems enable creativity by removing low-level decisions. Bad systems force creativity into rebellion.

Breath as rhythm. Vinyasa means breath-synchronised movement. One breath, one movement. The breath sets the pace. Systems that ignore team rhythm create friction. A design system that requires three-day review cycles for a button colour change breaks the team's breath. Match the system to the natural pace of work, not the other way round.

Constraints create safety. Props aren't shortcuts—they're precision. A block under your hand protects you whilst you build strength. Guardrails, not limits. A designer with 47 grey values makes worse decisions than one with five. The constraint removes noise.

Practice over perfection. You don't master yoga. You practise it. Design systems are never "done." Version 1.0 is the foundation, not the finish. The system evolves as the team evolves. Document what you learn. Refine what breaks. Retire what no longer serves.

Remove guesswork. The teacher demonstrates. Students follow. No ambiguity about what movement comes next. Systems remove repeat decisions—button styles, spacing rules, colour usage. Designers spend energy on problems, not pixels. Engineers build with confidence. Juniors ship without seniors as bottlenecks.

Systems That Breathe

Yoga survived 5,000 years because it's a system that breathes. Rigid enough to transmit across cultures and centuries. Flexible enough to adapt to individual bodies, teachers, contexts.

Design systems need the same quality.

Most teams build the wrong type. They jump to components without foundations. They build process without tools. They treat it like a project when it needs to be a practice.

Know your type. Practise what you need.

If you're early stage, focus on visual foundations (Type 1). If you're scaling, build the tools (Type 2). If you're mature, embed process and practice (Type 4-6). The path is sequential. You can't skip stages without creating imbalance.

Structure doesn't kill creativity. Rigid structure kills creativity. Structure that breathes enables it.

Foundations before flow. Repetition without rigidity. Constraints that protect. Practice over perfection.

Ancient systems solved this millennia ago. You're just relearning it with better tools.

Practical Takeaways

1. Diagnose your type. Don't build what you admire—build what you need.

2. Foundations first. Type 1 before Type 2. Alignment before advanced poses.

3. Match team rhythm. Fast teams need light systems. Regulated teams need heavier governance.

4. Constraints protect. Five greys beats 47. Fewer choices, better decisions.

5. Practice over perfection. The system evolves as the team evolves. Version 1.0 is the start.

6. Remove guesswork. If designers ask basic questions, foundations aren't solid.

7. Know your imbalance. Build the system your team needs, not the one that looks impressive.

ARTICLES